I recently presented this as part of a Research Conference at my school. I hope it proves interesting to readers here (this can also be read at my Moon In The Gutter). I'd like to dedicate this piece to the memory of Gordon Parks Jr., an gifted artist taken from us too soon whose place in American cinema needs to be reevaluated.

The strange saga of filmmaker Gordon Parks Junior’s Thomasine and Bushrod (1974) came to a tragic end on an April morning in 1979 when a small plane he was traveling in crashed into a Kenya mountainside. More than a decade later Parks’ father, famed photographer, poet and filmmaker Gordon Parks, remembered that the crash had been so bad that “only ashes” were left of his son making a proper burial impossible. The death of the younger Parks not only marked a eerie footnote to his most overlooked film, but also effectively ended one of the most controversial and misunderstood movements in Hollywood history.

The so-called Blaxploitation genre is often looked upon as a genre consisting only of urban films centering on negative stereotypes of African American culture made by white filmmakers. A deeper investigation into the genre reveals a treasure trove of mostly forgotten films shot, written by and starring African Americans, focusing on family, childhood, politics and civil rights, with none being more startling than Thomasine and Bushrod.

African Americans had appeared in Hollywood productions since the earliest films, but their roles were mostly relegated to ignorant sidekicks, apologetic caricatures and other harmful stereotypes. While there had been many independently produced African American films as early as the twenties, the ‘blaxploitation’ genre in the late sixties would mark the first time that African Americans would be given financing by major studios to make their own films. Thomasine and Bushrod is a particularly special production, as it was one of the earliest and only examples of a major Hollywood studio financing a film written, directed and starring African Americans in that oldest of genres, the western.

The story of Thomasine and Bushrod begins with Max Julien, a writer and actor best known for his role as the ambitious pimp Goldie in 1973’s The Mack. Author Darius James would note that Julien’s early life would be as far removed from his most famous role as possible and that he had “studied at Carnegie Hall’s Dramatic Workshop” and by his early twenties was appearing in “Joseph Papp’s New York Shakespeare Festival”.

Julien’s role in The Mack would make him an overnight star but the film, like almost all of the ‘blaxploitation’ films of the period, would garner as much derision as praise. Author Donald Bogle would argue that despite its popularity The Mack exemplified the problems with the movement and “was a mess without much of a script” and that it was “gaudy and cheap”. Still, others found much to admire in the film and the genre, such as film historian James Robert Parrish who noted that Julien was one of the genre’s shining lights and was “talented and charismatic”. Despite its many virtues and its success with audiences, The Mack was looked upon as by many as a film made by whites about blacks, something that Julien wanted very much to rectify for his next project. A meeting between Julien with a young up and coming actress shortly after The Mack’s premiere would plant the seeds for what would eventually become Thomasine and Bushrod.

Vonetta Mcgee was born in San Francisco in January 1940. After graduating from San Francisco’s Polytechnic High School in 1962 she became more and more interested in acting. After traveling to Europe, she began appearing in a number of Italian productions in the late sixties before getting steady work in a number of low budget exploitation films in the early seventies upon her return to America. Shortly after their introduction Mcgee became involved romantically with Julien, who was in the process of working on his first screenplay. The script, centering on an African American female version of James Bond named Cleopatra Jones, was quickly refashioned as a vehicle for McGee. Once the script was sold however to Warner Brothers, both Julien and McGee were removed from the project, which caused Julien to quickly write another script, a western called Thomasine and Bushrod.

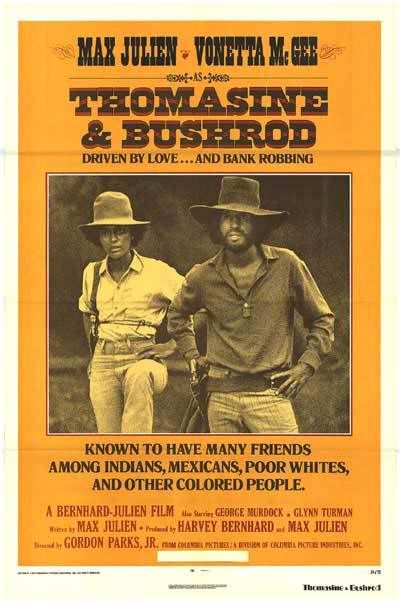

Max Julien’s original script for Thomasine and Bushrod is a confrontational and genre bending work posing as a take on Arthur Penn’s influential Bonnie and Clyde (1967). Focusing on a fictional outlaw in the old west named Bushrod and his partner in crime and love, a former female bounty hunter named Thomasine, who steals from the rich in order to help out various minorities, Julien’s script and the final film would delight in reversing gender roles, questioning accepted history and rethinking the western genre as a whole.

The script for Thomasine and Bushrod was bought by Columbia Pictures in 1973 and an agreement was made with Julien and McGee that they could both star in it as long they didn’t mind working with a relatively inexperienced director who had just scored a major success with his first film, 1972’s Super Fly.

Gordon Parks Jr. was born just a few weeks before Christmas in 1934 and life immediately proved difficult for the young man. His father would remember years later that “Gordon Jr. had developed a serious asthmatic” condition and that “doctoring didn’t seem to help”. The young Parks would spend much of his early life inside and under his father’s shadow but the two were always close and they began to collaborate on various artistic endeavors and civil rights activities in the mid sixties.

When his father, who had turned to filmmaking in the late sixties, scored big with his second theatrical feature, 1971’s Shaft, Parks Jr. was able to negotiate a deal to direct his first feature, which would turn out to be Super Fly. This production marked the first time the younger Parks would really make a name for himself and his short but intriguing film career that followed is an interesting mixture of his father’s early documentary work, his passion for photography and music and his interest in changing the way Hollywood viewed African Americans in film.

Thomasine and Bushrod is a flawed production, hampered by a quick shooting schedule on a low budget in a scorching New Mexico summer, yet remains downright ingenious in the way it confounds so many expectations. There are several things that separate the film from almost any other before or since with the most obvious being that it would have African American protagonists in the old west. The most daring move the film makes though is with MgGee’s character Thomasine who is placed in the clearly more traditionally masculine role. Not only does her name come first in the title, but the character of Thomasine is shown time and time again to be smarter, stronger, more controlled and more interesting than the weaker Bushrod. Julien’s script suggests strongly a rethinking of not only the Western genre in the placing of African Americans as the leads but also in its forceful questioning of clear gender roles.

Parks as a director obviously understood the subtleties of Julien’s script and how subversive it was. Filming McGee often from lower angles to give her power and authority while placing Julien much lower in the frame with the camera tilted down at him, Thomasine and Bushrod shows Parks to be a sensitive and intelligent stylist. This role as a stylist also distinguishes the film in another way, which is perhaps even more subversive than the gender and race relations it delights in subverting.

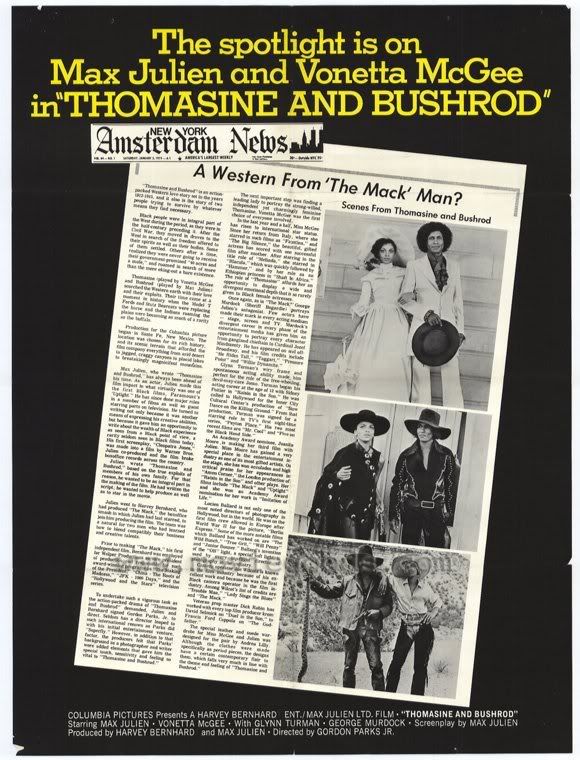

Thomasine and Bushrod's biggest attribute is one of its most surprising, that being how much Parks, Julien and McGee chose to highlight that it was a film made in 1973 about 1873. Not content with making a mere historically accurate piece, Parks fills nearly every frame of the film with visual references to the seventies, a move that makes it clearly more about the period it was made in than the period it was set in. The outlandish and stylish costume design by Andrea Lilly and Mcgee herself, the hair styles, the soundtrack (which features a title track by San Francisco band Love) and even some of the dialogue are clearly products of the seventies. Many critics mis-viewed this as laziness and lack of research on the part of Parks and Julien, but today it looks to be a clear headed and deliberate decision on their parts that goes along perfectly with the other subversive thematic elements of the film. Thomasine and Bushrod isn’t a film attempting to be historically accurate, it is instead a work that questions just what accuracy means in cinema.

The film is typified as the work of Gordon Parks Jr. by several visual motifs that he worked into all of his short filmography. These include a bittersweet slow motion love sequence and most notably a mid-film montage of still photographs of not only the actors but an extraordinary collection of rare shots of actual African Americans in the turn of the century old west. This section of the film is particularly important as it shows Parks not only marking himself as an auteur in the making but brings into question Hollywood’s continuing betraying of the historical events that critics accused Thomasine and Bushrod of ignoring.

Parks film was released briefly in the summer of 1973 with a half hearted ad campaign by Columbia attempting to capitalize on the real life relationship between Julien and McGee. The film failed to attract an audience and the critical community mostly ignored the production, although Nora Sayre in The New York Times found much to admire and picked up on how “utterly contemporary” the film was deliberately trying to be. The only other point of recognition came in late 1973 when Julien’s script was nominated for an NAACP award, which it lost.

Outside of a handful of television airings, Thomasine and Bushrod was pulled from circulation in 1973 and has never had a home video release. It is virtually a lost film. The films failure hurt all three of the main player’s careers. McGee has spent the rest of her career in mostly supporting roles while Julien dropped out of sight for nearly a quarter of a century. He resurfaced in the late nineties as his role in The Mack gained more and more popularity, but Thomasine and Bushrod remains his swan song as a lead actor and a screenwriter.

Gordon Parks Jr. completed just two more films, 1974’s Three The Hard Way and 1975’s Aaron Loves Angela, before losing his life in that Kenya plane crash of 1979 while scouting a new film. His father would write that television stations all over the world were “reporting my death” (336) instead of his sons marking the talented Gordon Parks Jr. as anonymous in death as in life. His Thomasine and Bushrod remains one of the great-unnoticed chapters in not only African American film history, but also American film in general.

2 comments:

This sounds really good. Great review. It's a shame that it's a pretty much forgotten film. I don't think I had ever even heard of it before.

Thanks Keith...I hope it hits DVD one day so more people can take a look at it...

Post a Comment